Over the next few days, Christian and Jewish families will be retelling stories of miracles and faith. Christmas and Hanukkah both focus on the idea of God bringing light into the world: either through the Jewish re-conquest of Jerusalem, which culminated in lighting the Temple's holy menorah; or through the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, who is “the light of the world” to Christians.

But as everyone who has lit a candle knows, a light shines brightest when it is kindled in darkness. The Christmas and Hanukkah stories tend to leave out the dark parts, but they’re there, just outside the margins, and they have valuable lessons to teach.

The Maccabean Revolt

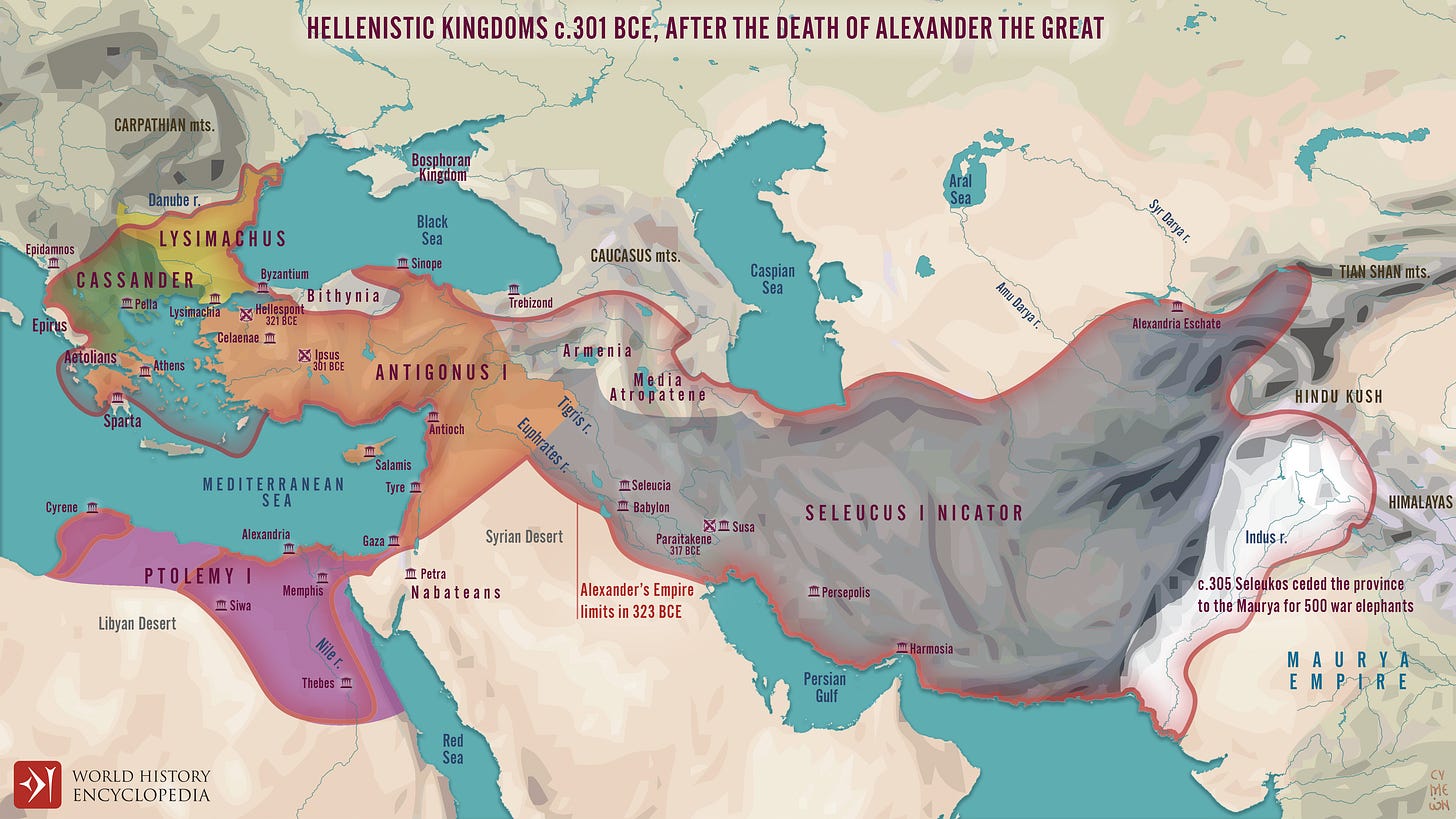

The Hanukkah story begins several years before the Temple menorah miraculously burned one night’s worth of oil for eight nights. Let’s set the stage: in 322 BCE, Alexander the Great died, leaving behind the largest empire the world had ever known. He left no clear heir, so administration of the Hellenistic empire was divided among several successors, as shown on the map below.

Within about 150 years, the Seleucid empire (in grey) had expanded far enough to the west to seize control of Judea (known today as Israel) from the Ptolemeic kingdom (in purple). The Seleucid empire was culturally Greek, but was based in modern-day Syria, so it is sometimes confusingly referred to as Syrian, and sometimes as Greek.

In any case, at that time, the Seleucid ruler was Antiochus IV, an aggressive monarch who had himself referred to as Epiphanes - “God manifest” - but who behind his back was called Epimanes - “madman.” Unlike other Hellenistic kings, who had collected taxes from Judea but otherwise left the Jews to worship as they chose, Antiochus IV was concerned that these “children of Israel” with their distinct language, religion, and culture, might revolt against him. As rulers have since time immemorial, he looked for ways to keep his opposition divided, so that it wouldn’t rise up against him. He soon found that there was a movement within Judea of what we might call assimiliationists: Jews who were big fans of Hellenistic culture, and who felt that that Jewish traditions like worshipping only one god and not eating pork were overrated.

These Hellenistic Jews were looking for ways to gain power within Judea, so they offered Antiochus IV a deal: if he backed their political efforts, they would raid the Temple treasury and pay him a handsome tribute. Antiochus agreed, but the Hellenists quickly ran into trouble with the more traditional Jews. In one awkward encounter, some Hellenists went to the town of Modi’in to demand that the residents sacrifice a pig to a pagan god. Instead, they wound up being sacrificed themselves. This particular plot twist was executed (pun intended) by a religious Jew named Mattathius and his sons.

Seeing that his local allies were running into stiff opposition, Antiochus IV decided to cut out the middleman and crush these annoying Jews the old-fashioned way. He outlawed Jewish worship and religious rituals (e.g., circumcision), and in 167 BCE, he looted the Temple, desecrating it and rededicating it to Greek gods.

Unfortunately for Antiochus IV, his oppression sparked the revolt he had been trying to prevent. Led by Mattathius and his sons Judah and Eleazar, the Jewish resistance retreated to the Judean mountains. From there, they launched a guerrilla war against the Seleucid empire and the Hellenistic Jews that supported it. The fact that they had a few hundred men, and Antiochus IV had a 70,000-strong army with artillery and elephants did not deter them.

Against such long odds, victory for a rag-tag army was far from assured. Mattathius died, Eleazar was killed fighting an elephant, and Judah - now nicknamed HaMakabi, “the hammer” - was left in sole command. By Divine Providence, Judah Maccabee turned out to be a brilliant tactician and a pioneer of asymmetrical warfare techniques. For example, he would attack sparsely-manned enemy bases while the enemy troops were out searching for him. The Seleucid soldiers would return to camp after hours of marching, hungry and tired, to find nothing but dead bodies and smoldering wreckage. Meanwhile, Judah and his men would have vanished back into the mountains.

Here’s where the more familiar Hanukkah story starts. After almost three years of fighting, Judah Maccabee and his men succesfully re-established Jewish control of Jerusalem. They re-dedicated the Temple (“Hanukkah” means dedication), and looked for uncontaminated oil to relight the sacred lamp. They only found enough pure oil for one night, but it burned continually for eight days and nights, which gave them enough time to get more oil.

In Jewish theology, there’s a saying: “In those days, at this time.” It refers to the idea that the stories told about the past are relevant to us today, and in ways that may not immediately be obvious. One element of the Hanukkah story that tends to get forgotten is that there were Jews on both sides of the conflict: those who wanted to abandon their traditions and join with the Greeks; and those who were willing to risk everything to preserve their religion and freedom. Antiochus IV exploited this internecine conflict for his own benefit.

In the same way, today’s “powers that be” encourage divisions and fractures among those who oppose them. Traitors are elevated to positions of authority, while those who demand freedom and truth are pushed to the margins.

Which brings us to the dark side of the Christmas story.

King Herod and the Babies

The Maccabean revolt was no flash in the pan: after Judah Maccabee died, his younger brother Simon completed the expulsion of Seleucid troops from Judea. In so doing, he established the Hasmonean dynasty - a century-long period of Jewish independent rule that ended with Roman conquest in 63 BCE.

As was typical for Roman colonies, local rulers were allowed to retain symbolic positions, but collaborators were put in charge of day-to-day administration of the region. In this case, the last Hasmonean King, Hyrcanus II, was stripped of political power, while an Edomite (descendent of Esau) named Antipater served as provincial governor. Around 40 BCE, the Roman Senate put Judea in the hands of Antipater’s son, Herod, naming him King of Judea.

Much like the Hellenistic Jews who supported Antiochus, Herod was Jewish, but his loyalty was to an outside power - in this case, Rome. A typical petty tyrant, Herod was obsessed with his legacy: he levied heavy taxes in order to fund grandiose building projects, and ruthlessly eliminated any potential threats to his throne - including by killing three of his own sons.

Whether King Herod ever ordered the massacre of baby boys in Bethlehem, as recorded in Matthew 2:16, is a matter of historical debate. While movies depict hundreds of babies being torn from their mothers’ arms and murdered in the streets, the small population of Bethlehem at that time (probably less than 1,000 people) means that there would have been very few boys aged two years or younger. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the total number of Holy Innocents was probably between six and twenty. Still terrible, of course, but by the standards of the time not necessarily noteworthy enough to record in a historical document.

Regardless of the truth of that particular event, in the person and actions of King Herod, we once again we see how lust for power was exploited by an established authority acting in its own self-interest. The Seleucids encouraged the Hellenists to make Judea more Greek, and Rome encouaged King Herod to make it more Roman.

In both cases, the assimilationists were opposed by a fierce leader: first Judah Maccabee, and then Jesus of Nazareth. When Jesus took a whip and drove the money-changers and dove-sellers out of the Temple, he was carrying on the Maccabean legacy of cleansing the holy space of impurity. It’s easy to understand why the Jewish leaders appointed by Rome saw him as a threat to their authority, and ultimately handed him - one of their own - over for crucifixion.

In Those Days, At This Time

The beauty of Biblical stories is that they are universally applicable. Judah Maccabee, King Herod, and Jesus of Nazareth were Jewish people who lived long ago, but the things they did and the lessons they teach can apply to every people, in every culture, in every time.

Whether you look at people who are Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, Muslim, black, white, Asian, Latino, gay, or straight, you will find different types of individuals: those who stand for freedom and righteousness, those who thirst for power and personal glory, and those who go with the flow, “standing for nothing but falling for everything.” No group is free of evil, and no group is devoid of good.

Therefore, it is fitting that, at the time of year when we celebrate light, we take a moment to reflect on what brings darkness. The Hanukkah and Christmas stories bid us to beware of the same things: divisiveness; abandonment of holiness in favor of false gods; pursuit of worldly things instead of spiritual ideals; collaboration with those who desire our destruction. All these pitfalls happened in those days, but they are very much with us at this time.

Looking Forward

As 2022 draws to a close, we face a world filled with uncertainty. A war in Europe threatens to engulf the globe, governments seem more interested in furthering the agendas of transnational organizations than in the welfare of their constituents, and it is becoming increasingly undeniable that interventions done in the name of COVID caused devastating physical and psychological consequences.

Against this backdrop, we need, more than ever, to seek the light. Instead of division, we must strive for collaboration. Instead of following false prophets in white coats or expensive suits, we need to renew our commitment to holy wisdom that has stood the test of time. Instead of allowing ourselves to be manipulated by entities whose interests are antithetical to our own, we must reconnect with that spark of the Divine that lives within each of us.

If we turn off the screens, shut our windows to block out the noise, and listen very carefully, each of us can hear the same, still, small voice that spoke to Judah Maccabee and Jesus of Nazareth. The one that brings comfort to our souls, and cheer to our hearts. The one that says “Fear not, for I am with you.”

To each of you reading this, I most sincerely wish you a Merry Christmas or a Happy Hanukkah. God bless us, every one.

Superb Essay. Privilege to read it; and the commentary based upon historical truth. A lot to chew on in this. Praying it will be shared far and wide among many diverse groups.

Excellent essay! Our family are traditional Catholics and, we too, are striving to continue our traditions as they have always been.

Each Advent, since the kids were little, and still today with the youngest being 18, we have read 2nd Maccabees, a little each night for a few nights, until it’s over. This is in addition to the Advent related scripture and commentary we read nightly around the lit Advent wreath. The boys (and even a couple of the girls) were always able to point out certain similarities between that story and the Advent story.

We treat Advent as a time of penance, though much lighter than that required during Lent. The Birth occurred very near the winter solstice so the days were already short and the dark night long.

In the midst of that darkness, the Light was born and the darkness could not overcome it.

My husband is an ethnic Jew and converted in 2009. It’s fascinating to see the parallels between the old and New Testaments.

Happy Hannakuh (I can never remember the spelling) and Merry Christmas to all!