Everything Is a Trade

So don't be a sucker

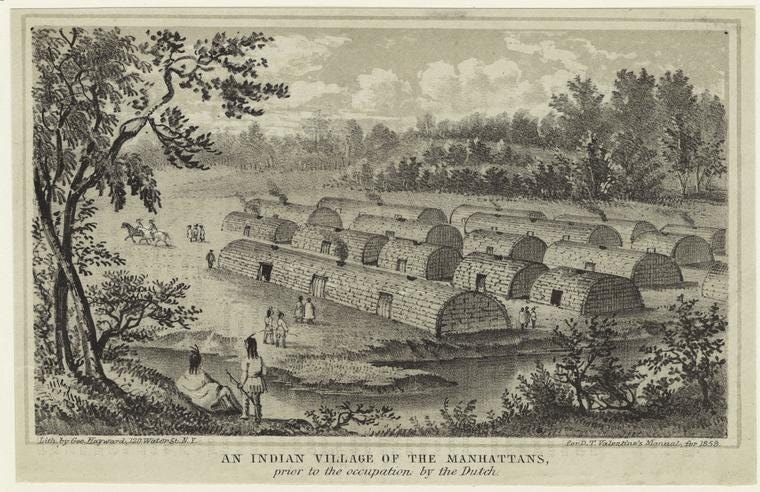

In 1626, the Lenape tribe traded Manhattan island to the Dutch West India Company for 60 guilders worth of tools and trinkets (roughly $400 in today’s money). The 2011 movie “In Time” depicted a future in which lifespan itself is used as currency; workers are paid in minutes of life, and trade those minutes for things they need.

As has been noted, “there’s a sucker born every minute.” The question is, how do you avoid being one?

Being a sucker usually means being taken advantage of in some kind of exchange. Life is full of opportunities for this, since every decision we make involves a trade. That, in itself, is not the problem. The problem is that, too often, we don’t measure the value of what we’re giving up compared to what we’re gaining. Sometimes, like the “In Time” characters, we feel we don’t have a choice. More often, like the Lenape, we just don’t recognize how what we have.

In “In Time,” age and life are electronically controlled. Everyone stops aging naturally at 25, and their continued existence is regulated by some kind of electronic implant that stores their time. A wealthy person could have thousands of years stored in the bank. A poor person might barely earn enough minutes to survive from one day to the next. When your digital counter reaches zero, poof - you instantly drop dead.

This is a heavy-handed metaphor perhaps, but a compelling and accurate one. In the film, the workers may have been exploited by a system that kept them running on a treadmill they could never escape, but at least they understood the deal. The Lenape did not. One might argue that makes them the bigger suckers.

Nassim Taleb, author of “Black Swan” and “Antifragile,” has a lot to say about suckers. In his opinion, the key to being a “nonsucker” is not intelligence or even skill, but simply the ability to predict the outcome of a situation. “The need to focus on the payoff from your actions instead of studying the structure of the world has been largely missed in intellectual history,” he writes in “Antifragile,” “The payoff, what happens to you (the benefits or harm from it), is always the most important thing, not the event itself.”

“In Time” gets the “payoff” point very right. In life, the basic unit of value is time - or, more precisely, energy. To what do you direct your physical labor, your mental horsepower, and your emotional vigor? What are those things worth, and what do you gain in return? What is the payoff for the one thing you have to trade?

Of course, measures of value are are subjective. Writing the Great American Novel might be important to you, while daily family dinner might be more important to me. We only have so much time, so what you choose to spend it on?

One of the great tragedies of the electronic age is that our devices make it easy to squander our time and energy. How much life-force does it take to earn a high score on Candy Crush, and what else could you have used it for? To put it in Taleb’s terms, does trading your life away, a few minutes at a time, for some ephemeral electronic diversion, make you a sucker? It would be difficult to argue that it doesn’t.

The Lenape Indians had no way to foresee skyscrapers and subways. To them, the bountiful Earth was unlimited, so if these pale new neighbors were willing to give them a few beads and hatchets in exchange for an imaginary claim to a small portion of it, why not take the deal? In retrospect, perhaps it wouldn’t have mattered if they had tried to negotiate more aggressively. At some point, it would have been easier for the Dutch to simply kill them than to trade with them. Were they really suckers, or did they actually make the best of a bad situation? One could effectively argue either position.

The rebellious protagonists of “In Time” monkeywrench the system of oppression by stealing millions of hours from the rich and giving them to the poor. In the short-term, that’s a gratifying payoff. In the long-term, who does the jobs they have abandoned to their new lives of leisure? Who are the suckers in this situation, really?

Thankfully, most of the trades we face are neither so complex or so consequential. Every day provides us with opportunities to direct our energy towards things we find valuable, or to divert those irreplaceable minutes into things that simply amuse us. The choice is ours. And, for better or worse, so is the payoff.